The Social Side of Capital

Inferring Connections Between Portfolios

By James Padkin

ESG, SRI and Impact investing. What are they, and why are they important to today’s investors?

Introduction

Investors have traditionally deployed capital in order to generate returns on a purely financial basis. This is beginning to change. Increasingly, engaged investors, both retail and institutional, are seeking investments whose performance is measured not only in terms of economic return, but also in terms of real-world societal and environmental impact.

The practice of investing with a ‘conscience’ has grown significantly since the turn of the century. Catalysed by an increase in public ignominy towards corporates, itself driven by a form of accelerating techno-cultural progressivism. With almost daily frequency, examples of environmental negligence, social inequity and corporate governance disasters heighten public (and shareholder) sensitivity towards such issues - the moral failings of globalised corporations are increasingly difficult to ignore.

With interest in ethical and sustainable investment opportunities surging, a class of strategies have emerged whose mandates and investment philosophies seek to integrate a range of non-financial factors into their investment theses.

By non-financial factors or ‘themes’, we mean a collection of often intangible and hard to measure criterion, encompassing everything from climate change, carbon emissions and energy, through to diversity, labour rights and executive compensation.

New kids on the block

In recent years, several closely related strategies have emerged as alternative approaches to traditional, value-driven investing. They are socially responsible, ESG and impact investing. All three incorporate non-financial factors in addition to, or as an alternative framework to fundamental economic analysis, pricing anomalies and speculation. All three seek to integrate a values-driven dimension into the investment process, yet they are also distinct in their scope and application.

SRI and ESG

‘Socially responsible’ investing (SRI) has been around for a long time, but it wasn’t until the 1960s and 1970s that it began to gain traction as a credible investment strategy on the back of significant societal and environmental protest movements. Facing increased public scrutiny, investors began to adopt negative screening methods excluding investments in ‘sin stocks’ from their portfolios, including, arms, tobacco, gambling, adult entertainment and other activities considered ethically questionable.

Companies engaged in activities relating to environmental destruction, animal rights violations and the so called ‘military - industrial complex’ also came under fire. Investing in these businesses was increasingly viewed negatively, leading some investors to re-consider their investment portfolio on moral grounds in an attempt to avoid public ignominy.

Socially responsible and ‘ESG’ investing are often considered synonymous. If anything, ESG has emerged as a sub-set of SRI. Where SRI focuses on asset screening driven by subjective moral norms, ESG investing seeks to objectively evaluate non-financial characteristics of companies as potential risk factors. Using proprietary ESG analysis or third-party ratings frameworks, investors and fund managers can select companies on the basis of how they score across a wide range of ESG criteria.

Challenges and progress

Critics of ESG ratings will assert that they are intrinsically difficult to standardise, in part due to the complex and nuanced nature of companies. In talks about ESG ratings, Hester Peirce, a commissioner at the American Securities and Exchange commission said they were “labelling based on incomplete information, public shaming, and shunning wrapped in moral rhetoric”.

While some factors are straightforward to quantify i.e. volume of carbon produced, there are considerable challenges with, for instance, defining and quantifying social impact. With ‘S’ metrics ranging from wages to employee satisfaction, and the effectiveness of grievance procedures, it’s no surprise that ESG ratings are a contentious topic. Analysis performed by The Economist investigating the correlation between ESG ratings provided by two different major ESG rating agencies showed “at best a loose link” between the ratings given by each.

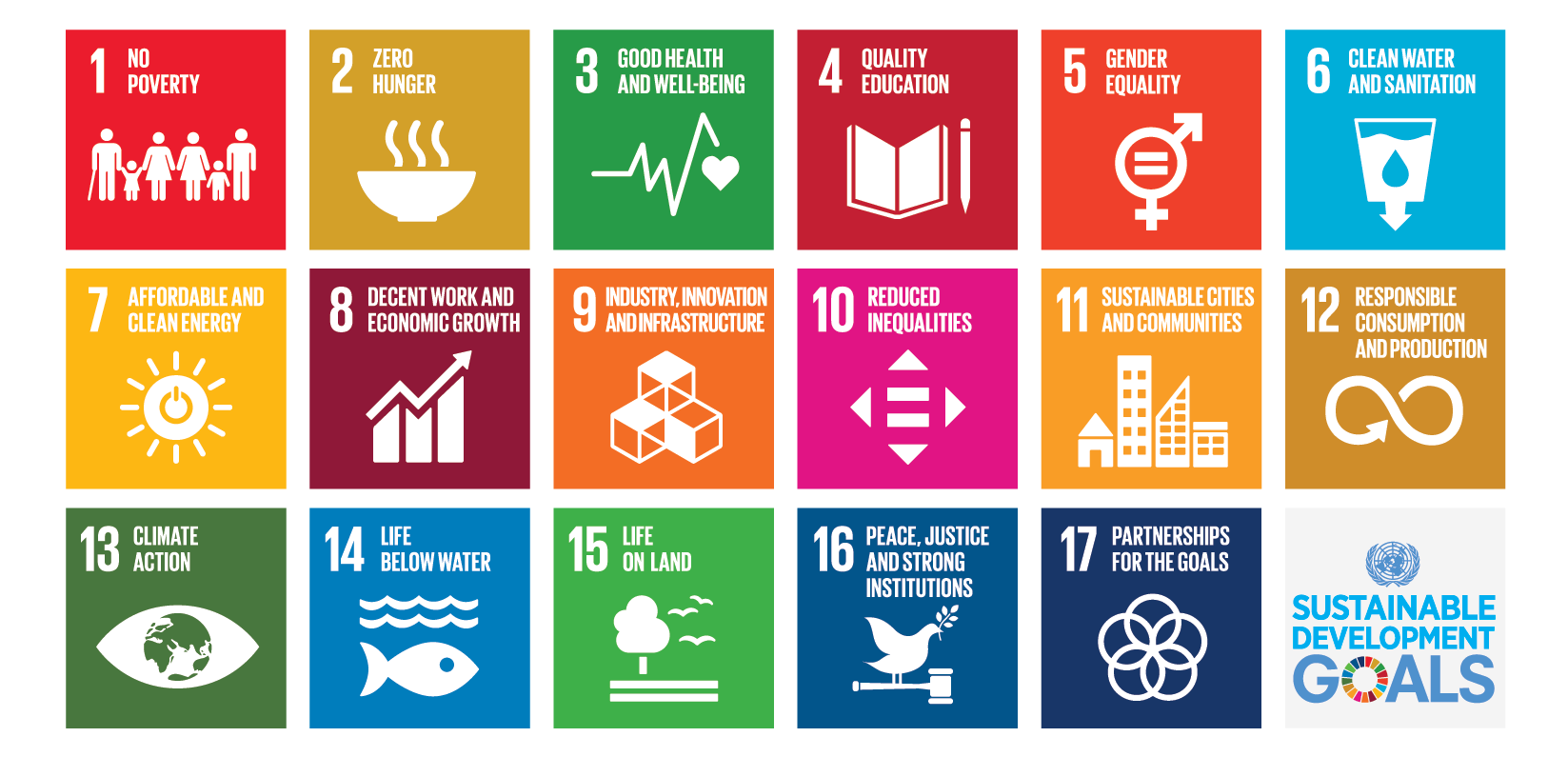

The UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), launched in 2015, as well as the Paris Agreement, signed in 2016, have been and will continue to be instrumental in bringing critical socio-economic and environmental issues to the forefront of the minds of the public, as well as helping to galvanise regulatory support and specific targets for governments and institutions. But clearly, there is work to be done before ESG methodologies and ratings can be standardised and applied consistently.

Uptake

It is a common misconception that socially responsible or ESG investing produces lower than market returns. In fact, many investors consider investing in companies with strong ESG characteristics a portfolio risk reduction exercise, partially due to a lower exposure of these companies to stranded assets. Furthermore, ESG factors such as ‘energy management’ or ‘employee wellbeing’ can be credible indicators of the longevity and potential financial performance of a company.

Research has demonstrated that investments with high scoring ESG credentials have the potential to drive returns, while those with poor ESG performance may actually inhibit returns.

Taking the ESG bull by the horns is the PRI (The Principles for Responsible Investment), an independent, global network of investors. Supported by the United Nations, the PRI lays out six principles for sustainable investment and works to understand the investment implications of ESG factors as well as supporting its signatories in incorporating these factors into their investment decisions.

Since its inception in 2006, the PRI has grown from 100 signatories to over 3,000 in 2020. These signatories operate across a range of asset classes including listed equities, fixed income and private equity and have combined AUM (Assets under management) of over $100 trillion, highlighting the interest in ESG investment and its prevalence in the investment landscape today.

Impact

‘Impact’ investing is often considered the most sophisticated and challenging of the three approaches. There are investors in this space to whom generating targeted, measurable environmental or social impact is paramount, with financial returns of secondary importance.

Impact investing is the process of investing capital in such a way that it creates or contributes to positive outcomes, for society or the world at large. Impact investment opportunities span a growing list of issues and activities relating to education, energy, water or healthcare, affordable housing, renewable energy, micro-finance and many more (see UN SDGs).

Impact-driven investments can be made into a variety of asset classes in both emerging and developed markets with returns ranging from below market to market rate targeted, depending on investors' strategic goals and risk appetite.

There are a number of fundamental challenges for investors in this space. How can impact, particularly of a social nature be measured? Can impact be quantified, not only in terms of itself, but also as a function of time i.e. sustainability? How can investors be sure of not inadvertently worsening the very issues they seek to tackle? Unintended consequences not considered or modelled in pre-investment research may have amplified negative consequences down the line. Furthermore, which of the UN’s 17 SDGs are most critical, or perhaps deserving of impact investment? What markets or communities offer the best chance of positive impact as a return? How is that worked out and, how much capital is required before such impact emerges?

Of course, much of this is subjective and depends entirely on the appetite and aspirations of the investor.

Final remarks

Ethical investing will continue to grow as increased numbers of investors adopting such approaches become more prevalent and influential in the market. However, profit and impact can be challenging to achieve in unison, and whilst creating both to any meaningful degree is certainly possible, optimisation of one may conflict with and have a detrimental effect on the other.

Success in this space hinges on identifying investment opportunities where financial performance and positive environmental and socio-economic impact are sustainable and balanced. SRI, ESG and Impact methodologies and strategies are increasingly important tools in helping today’s and tomorrow’s investors locate those opportunities.

By modelling and classifying a range of ESG related themes, and then mapping these to institutional investor behaviour, Irithmics’ AI helps organisations across the capital markets eco-system understand, anticipate and leverage the contextual factors shaping the views and expectations of investors.

If you would like to find out more, please get in touch.

James Padkin co-wrote this article as part of an internship with Irithmics. He is a recent chemistry graduate with an interest in finance and sustainability and has previous internship experience in renewable energy investment.

Schedule a demo or get in contact for more details.

Get the latest on products updates, research and articles.